In addition to being the cruelest month (thanks, T.S. Eliot), April is National Poetry Month, and if I’m deliberately passionate about anything, it’s poetry. A lonely passion, one shared almost exclusively by fellow self-identified poets, which feels exactly right.

In case you’re wondering, here are a few things I’m not deliberately passionate about but passionate about nonetheless:

- Correcting two spaces after a period

- Evangelizing Oxford commas

- Highlighting terrible accents (among others, I’m looking at you, Anna Paquin, as Sookie Stackhouse)

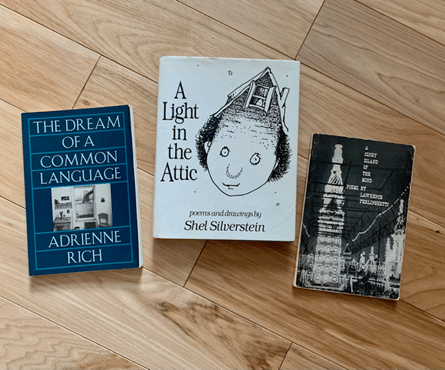

My all-time favorite poetry collection is Adrienne Rich‘s 1978 stunner The Dream of a Common Language. In it, Rich uses her bold, unapologetic voice to bring the experiences of women—whom she saw being pushed to the margins, especially queer women like herself—to the center of the page (did I mention I have an MFA in Poetry?). I discovered Rich’s work in high school, at the same time I was emerging fully from the closet. My introduction to her was “Diving into the Wreck,” which you can listen to Rich herself read here, but the poem I always return to, the one that awakened in me what it meant to be a budding baby dyke, the one we incorporated into our lesbian wedding vows, is “The Floating Poem, Unnumbered,” from her “Twenty-One Love Poems” series.

(The Floating Poem, Unnumbered)

Whatever happens with us, your body

will haunt mine—tender, delicate

your lovemaking, like the half-curled frond

of the fiddlehead fern in forests

just washed by sun. Your traveled, generous thighs

between which my whole face has come and come—

the innocence and wisdom of the place my tongue has found there—

the live, insatiate dance of your nipples in my mouth—

your touch on me, firm, protective, searching

me out, your strong tongue and slender fingers

reaching where I had been waiting years for you

in my rose-wet cave—whatever happens, this is.

From “Twenty-One Love Poems,” from The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977 by Adrienne Rich. Copyright © 1978 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Before Rich, my poet love was Lawrence Ferlinghetti. My first self-acknowledged same-sex crush, Jacqueline (who went by Jackie), a fellow student at Summer Ventures in Science and Mathematics when I was 16, introduced me to the Beats, especially angst-ridden Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. But it was Ferlinghetti—a publisher of the Beats more than a Beat himself—who stole my heart. I scoured used bookstores and antique shops for his titles, and though I have an extensive collection of his works and even a couple of original printings, the two I go back to over and over are Her, a semi-autobiographical novel, and A Coney Island of the Mind, especially “Dog.” I’ve included the beginning below; you can read the full poem here.

Dog

The dog trots freely in the street

and sees reality

and the things he sees

are bigger than himself

and the things he sees

are his reality

Drunks in doorways

Moons on trees

The dog trots freely thru the street

and the things he sees

are smaller than himself

Fish on newsprint

Ants in holes

Chickens in Chinatown windows

their heads a block away

…

Excerpt from “Dog” from A Coney Island of the Mind: Poems. Copyright © 1958 by Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

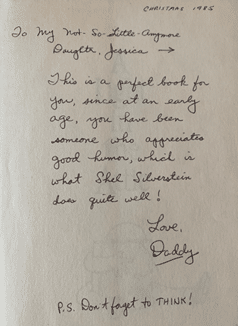

And before Ferlinghetti, there was Shel Silverstein. Most kids I knew loved The Giving Tree best (depressing as fuck) or Where the Sidewalk Ends (definitely a good one), but A Light in the Attic was always my favorite. My father gave it to me for Christmas in 1985. I know because he inscribed it. I was still small then, and I didn’t have the words for the things I make it a point to name now. I didn’t know how to name anxiety or depression or the many fears that hounded me, but I knew how to deflect. I cowered at my father’s temper that flared up at imaginary infractions and tried to laugh them off if my friends accidentally bore witness. I couldn’t articulate the ways my father had touched me and my brother E, the parts of him that he’d rubbed on the parts of us, all of it shrouded in shame that should have been his but that I carried (sometimes still carry) for us all. Even what my father inscribed to me, loving and warm as it seems, betrays a maturity that seems almost unnatural given that I was only 8.

My favorite is the title poem of the book, and when I read it now, I see it in a new light (pun accepted). What a lost little inside-out girl I was.

A Light in the Attic

There’s a light on in the attic.

Though the house is dark and shuttered,

I can see a flickerin’ flutter,

And I know what it’s about.

There’s a light on in the attic.

I can see it from the outside,

And I know you’re on the inside…lookin’ out.

From A Light in the Attic. Copyright © 1981 by Shel Silverstein.

When Lawrence Ferlinghetti died in February just a month shy of what would have been his 102nd birthday, I was dumbfounded and—dramatic though it sounds—devastated. It had seemed to me that he would live forever. But more than that, I was grateful. Grateful to have been introduced to his work. Grateful that I got to see both him and Adrienne Rich (not together, though how awesome would that have been?!) read at the 92nd Street Y in New York City. Grateful that he seemed kinder and softer and more human than Allen Ginsberg, whom I met in person my senior year of high school and was underwhelmed.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that poetry—reading and writing it—has been a lifeline for me. Rich, Ferlinghetti, Silverstein were my first poetry loves, but many more have and will come after them.

Yours in poesy,

Jessica the Westchesbian