Every year on December 1, World AIDS Day, I think about Steve, and this June, as we mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising and welcome WorldPride to NYC—WorldPride’s first time in the US—he’s been on my mind a lot, too. Because while we celebrate how far we’ve come, we must also remember those we’ve lost along the way, especially under this current administration that has put many queer people, myself included, on edge. Literally on edge. For some of us, it feels like we’re teetering on a precipice; others have already been shoved off. The transgender community is under particular attack. If you haven’t been paying attention to the ban on transgender troops legislated via Twitter in 2017 and put into effect in April of this year, you should be. It’s kind of like Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell but more targeted, openly bigoted, and built from a White House of cards made of lies (yes, that’s a terrible metaphor but not wrong). If you haven’t been paying attention to the violence against trans people and trans women specifically, trans women of color more specifically, and black trans women most specifically, you should be. At least 10 trans people have been violently killed this year already, all of them black trans women.

I say all of this as someone who’s acutely aware of my own privilege and the privileged queer experience it has afforded me to date. I’m cisgendered, white, and came of gay age (gayge?) in the early 1990s in a progressive Southern town, which sounds like an oxymoron because it kind of is, that had four—count ’em, four!—gay bars, two of which were 18-and-over clubs (they were named, I shit you not, Scandals and Hairspray—I know). I’m also Jewish, which I mention because there’s no shortage of Jewish lesbians—I think we might actually be a prerequisite for progressive Jewish families.

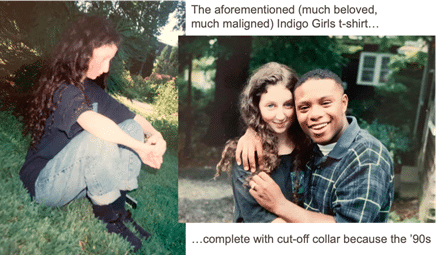

That’s not to say it was all sunshine and rainbow flags. It was still North Carolina, and it was still the 1990s. Boys in my class were mercilessly bullied—verbally and physically—for being too feminine. Our health textbooks, which were from the 1960s, referred to homosexuality as a mental disorder, though that language had long been removed from the DSM. And as early as junior high, before I’d consciously considered my sexuality, I was “jokingly” referred to as an Indigo Girl-listening, man-hating, feminazi lesbian because of my politics and choice of t-shirts (Harvey Gantt was running against Jesse Helms for the Senate, and a very forward-thinking social studies teacher had us hold a mock debate, which revealed unsurprising political fissures among our eighth grade class). I think it’s fair to claim I was more aware than most people my age of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and was one of a handful of high school students and the only one from my high school to volunteer with the Western North Carolina AIDS Project (WNCAP), during which complications from AIDS became the leading cause of death among adults 25 to 44. Anyway, it could have been much, much, much worse and was for many, many, many other people, but it was during a less-than-rainbow time that I met Steve.

Steve was the costume designer for the 1994 Asheville Community Theater (ACT) production of Bye Bye Birdie. I was 17 and miserable, which I guess is really the same as saying I was 17, cast in the play by my high school chorus director (with whom I feel I should mention I’m still in close touch and have even stayed with him and his husband on visits back to Asheville) along with the rest of the “advanced women’s choir,” who had shut me out after I made the mistake of telling one fellow member, Jennifer, during a sleepover at my house that I had crushes on girls and boys, only after she’d told me the same. Of course, it was a trap, and by Monday, she’d told the entire rest of the choir and started spreading rumors that my best female friend, Laura, and I were lovers. I was self-identifying as bisexual at the time, so it felt dishonest to try to fully quash the whispers, though I was sure to clarify to anyone who asked that Laura and I were absolutely not together. Laura was mortified and had to explain to her dumbass boyfriend that the rumors were patently false. I should have known better than to confide in Jennifer. She was something of a bully, but if I’m being honest, she was also kind of hot, and I think my little lesbian heart thought, Maybe, just maybe. Where’s Admiral Ackbar when you need him?

It was a summer production, which meant spending long hot days singing and scene blocking and explaining to the choreographer that no, I was not going to be able to do some crazy gymnastic chair dance during “The Telephone Hour” (a gossipy number in which I had a semi-ironic mini-solo, “What’s the story, morning glory? What’s the tale, nightingale?”), and being whispered about across the cast because the chorus girls couldn’t stop telling people that I was a big fucking muffdiver and they better watch out if they were girls and watch out for their girls if they were boys (all of which I knew because I’m not a moron and can tell when people are staring and pointing and laughing but also because I did have a couple of friends in the cast—Heather, a sweet Christian girl who was the only choir member who kept talking to me, and Kellmeny, a fellow theater kid—who would report to me all the bullshit being spread backstage). Steve was warm and welcoming right away, gay as the day is long and likely identified the same gay-long day in me. I realize now he must also have seen how uncomfortable the whole backstage situation was for me; he would frequently pull me aside and bring me to the back of the theater just to chat. He made me a custom costume that included capri pants instead of a ridiculous poodle skirt that would have felt like drag. He showed me where I could change without having to undress in front of all the other girls, which was a comfort not just because I was super self-conscious about changing in front of anyone but also because the chorus girls had made it clear that no one should feel comfortable changing in front of me.

Steve and I didn’t stay in consistent touch after Bye Bye Birdie, and I quit halfway through the show’s run in order to go to the North Carolina Governor’s School to study poetry (so gay). But Asheville was a small town then with a small theater community, and I would run into Steve and his boyfriend from time to time. I didn’t know he was sick until he came into the Olive Garden for dinner one night when I was working (if you can believe it, I was a hostess and a damn good one at that), and I saw the lesions on his face and felt his frail frame when we hugged for the last time.

Steve lived another year after that encounter, but I didn’t see him again and learned of his death from the newspaper. I was home for my first summer during college, and my father said, “Hey, didn’t you know this guy?” It was the first obituary I’d ever seen for someone I knew, and I kind of wish I’d kept it. There in black and white in the Asheville Citizen-Times was a picture of Steve in healthier days followed by mentions of his theater work, vague references both to his longtime companion and his death being due to complications from pneumonia (not technically false but not the whole truth either), and details on the time and location of his memorial service.

There are summer days in the mountains of North Carolina that are warm without being hot and breezy without being windy and sunny without being too bright, and you find that you understand what being “nestled” means. I know you’re thinking there are days like that everywhere, but I assure you, there aren’t. A cloudless Carolina blue sky really is a different color than any other blue sky, and a Blue Ridge Mountain summer day like the one I’m trying to describe is as close to perfect as I think I’ve ever experienced. Steve’s memorial was on a day like that.

It was held outside on the grounds of All Souls Cathedral, an LGBTQ-friendly Episcopal church even back then. The cathedral, which sits not far from my high school, in the center of Biltmore Village, was built in the late 1800s by George Vanderbilt to be the parish church for his Biltmore Estate. It is somehow both simple and opulent, designed—like the Biltmore House and a myriad other Vanderbilt homes up and down the East Coast—by Richard Morris Hunt in neo-Romanesque style with simple arches, hand-blown stained glass windows, and Westminster Peal bells that toll on the half hour. When we walked into the sanctuary, we were each handed a little white box with a purple ribbon and then led outside, where there was a podium set up and about 100 wooden folding chairs, all of which were filled by the time the service began.

I don’t remember much about the service itself except that the pastor was warm and seemed to genuinely know Steve—I’ve since been to several funerals where it’s clear the clergy and the deceased had no prior relationship, which feels deeply disrespectful to me even if these services are for the living and I don’t believe in any kind of afterlife—and that after Steve’s family shared their love and memories of him, all those in attendance were given an opportunity to speak, which I did. What I remember vividly, though, and what I have carried with me all these years is how the service ended. Once the speakers had finished, we were told to hold up the little white boxes we’d been handed when we walked in, and we were guided to—all at once—untie the purple ribbons. As the flaps of the boxes fell away, there was a rush of little wings. Butterflies. Dozens and dozens and dozens of butterflies.

Now, maybe you knew this was a thing, butterfly releases at funerals; maybe you knew what was in the box as soon as I mentioned it. I didn’t. At 19, this was only the second memorial service I’d ever been to, the first being for a high school friend who died in a car accident when some motherfucker ran a red light and slammed into her while she was making the notoriously precarious left turn onto New Haw Creek Road, where you always waited for the green arrow, always always, because people fly down that section of Tunnel Road. She was five minutes from home, having waited patiently for the green arrow, when his pickup truck barreled through at 50 miles an hour, crushing her little sedan and dragging it 100 feet. The thing I remember most about her funeral is that they played Enya’s “Sail Away” (technically titled “Orinoco Flow,” according to Wikipedia), which ruined that song for me long before it was overused in TV commercials for Crystal Light and various cruise lines. Anyway, the point is, I had no idea releasing butterflies was a thing. I had no idea the transformational symbolism they carried on their feather-soft wings, and it’s rare since Steve’s memorial that I see a butterfly and don’t think of that moment.

To Those We’ve Lost, Rest in Power,

Jessica the Westchesbian

Jessica lives with her shiksa wife and geriatric cat in picturesque Tarrytown on the Hudson. Although a proud Westchesbian these days, Jessica grew up in Asheville, North Carolina, back when the opening of the Olive Garden and the 24-hour Walmart were big news. During business hours, Jessica’s a communications professional who translates highly technical concepts into clear, concise, colloquial language that media buyers and sellers can understand. Outside of business hours, she’s a poet, cat mom, wife, avid reader, and lover of questionable crime, sci-fi, and supernatural TV shows (preferably all in one), not necessarily in that order. Her poetry has appeared in Tin House, The Paris Review, LIT, and The Huffington Post, among others.